21.10.2022 – 31.10.2022

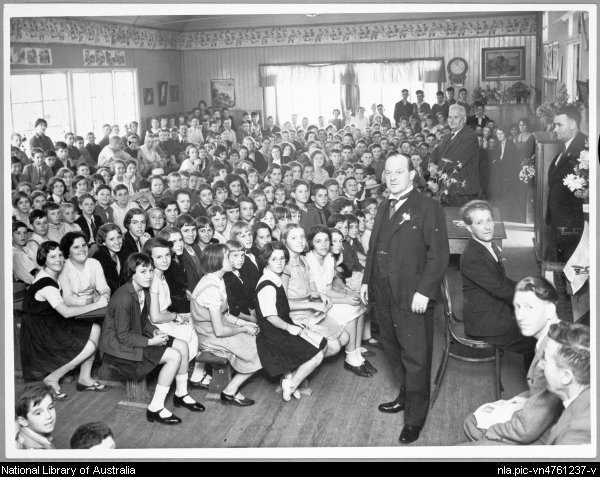

XII Darmstadt International Chopin Piano Competition

Awards Ceremony and Prizewinners’ Concert

After nine days of competition for prizes totaling €30,000, the six main prize winners played a celebratory final concert. On the program: solo piano works by Chopin and improvisation

For detailed information about this concert which took place on

October 31st at the Orangerie, Darmstadt at 19.00

https://chopin-gesellschaft.de/events/event/xii-darmstadt-international-chopin-piano-competition-prizewinners-concert/

Running assessment of the Competition

Shigeru Kawai piano is used exclusively

Official Results of the Competition

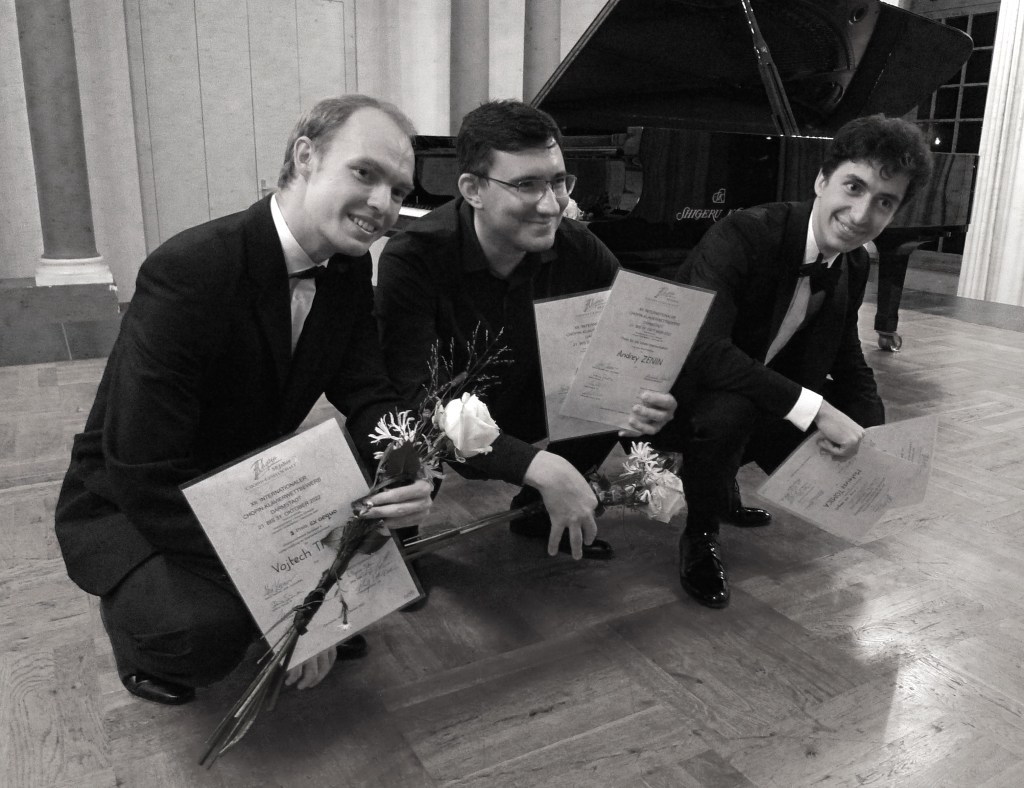

A First Prize was not awarded

Second Prize ex aequo:

Mateusz Tomica (Poland) Vojtech Trubach (Czech Republic)

Third Prize: Andrey Zenin (Russia)

Fourth Prize: Da Jin Kim (South Korea)

Fifth Prize: Fantee Jones (USA/Taiwan)

Sixth Prize: Zvjezdan Vojvodic (Croatia)

Prize for the Best Mazurkas: Mateusz Tomica (Poland)

Prize for the Best Improvisation: Andrey Zenin (Russia)

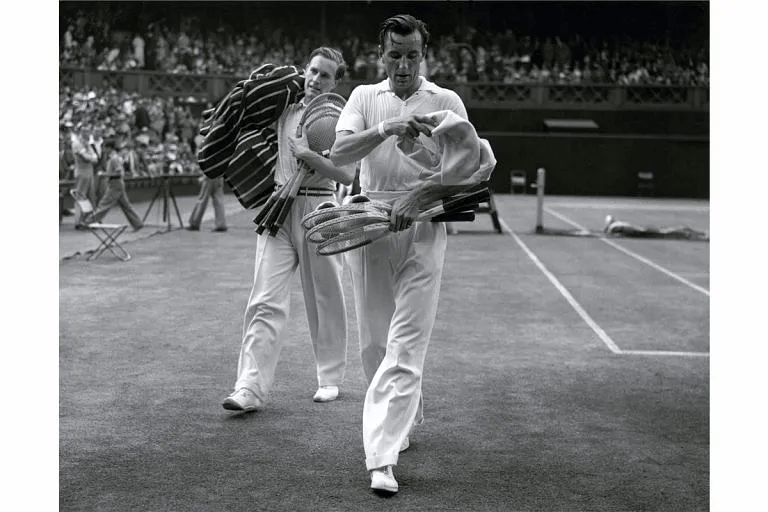

From Lt. Mateusz Tomica, Vojtech Trubac, Andrey Zenin, Da Jin Kim, Fantee Jones, Zvjezdan Vojvodic

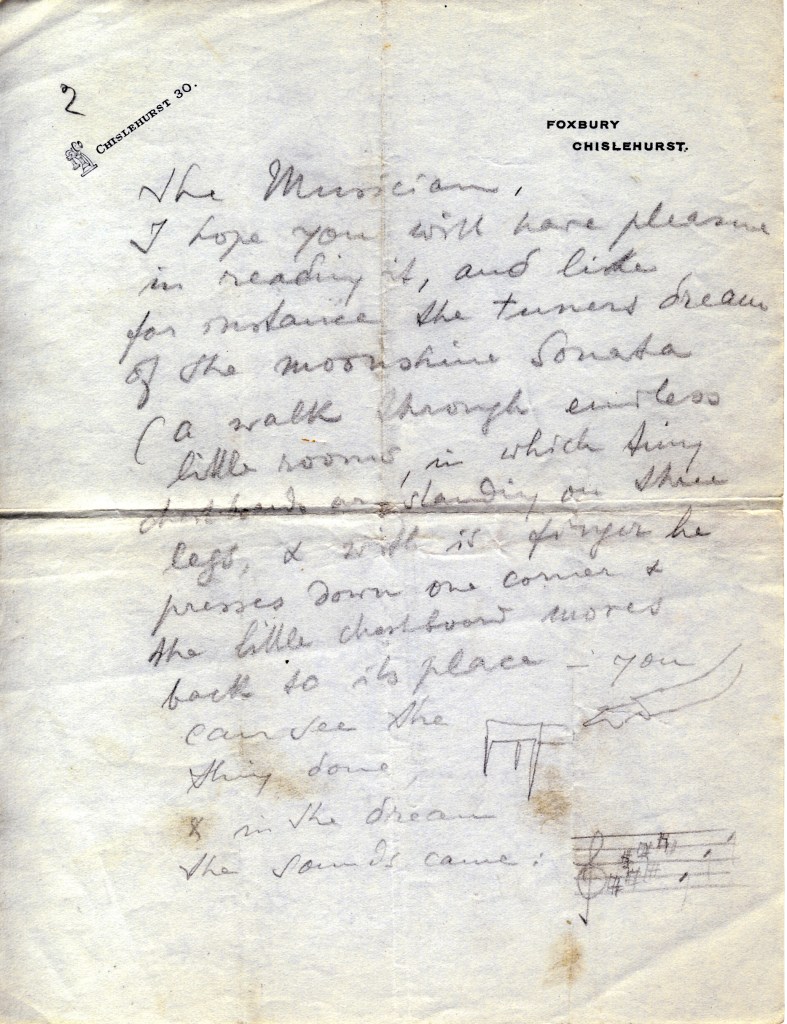

I anticipated this result but felt the missing First Prize award was, with all the best intentions, an error of public relations rather than music. I thoroughly enjoyed the entire competition as I met on unexpectedly intense terms, some of the most outstanding professors, teachers and pianists of my generation.

I simply reflected that for the conventional music-lover, not awarding a First Prize to any candidate in this competition indicated that none of them were sufficiently outstanding to deserve a First Prize. This is not entirely true for me as interpretation has become increasingly standardized of late, but then I am neither a musicologist nor professor of music, simply a literary author and lecturer who studied the piano and harpsichord seriously. I must try and make the candidates ever so slightly less deadly serious about their competitive task. Life is to take joy from as well as to study hard.

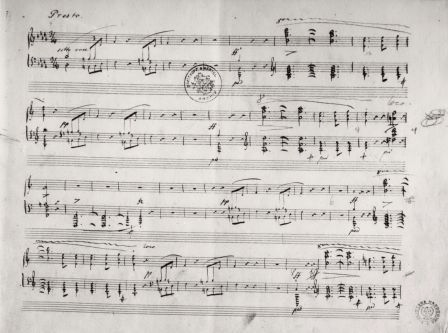

I felt the inclusion of an improvisation stage was a rare and profitable musical excursion for young pianists into a world completely familiar to a composer-pianist such as Fryderyk Chopin and many other great composers before and after him.

Finals

WORKS FOR PIANO AND ORCHESTRA

Saturday, 29.10. and Sunday, 30.10.2022,

18:00-21:00

Orangerie, Bessunger Str. 44

Works for Piano and Orchestra by Chopin

Piano Concerto in F minor, op. 21

The orchestral part was performed by the Polish string quartet

„Apollon Musagète Quartet“ and Sławomir Rozlach, double bass.

The following candidates advanced to the

Third and Final Concerto Stage

| No. | Name |

| 16 | Jones, Fantee – USA/Taiwan |

| 17 | Kim, Da Jin – South Korea |

| 39 | Tomica, Mateusz – Poland |

| 41 | Trubac, Vojtech – Czech Republic |

| 42 | Vojvodic, Zvjezdan – Croatia |

| 48 | Zenin, Andrey – Russia |

As the modest competition reviewer, I feel I really must say a few personal words about how highly enjoyable this competition has turned out to be.

The pleasure and joy of making music in the name of Fryderyk Chopin by these highly talented candidates is tangible in their obvious camaraderie and intense group motivation. The members of the distinguished jury, all eminent professors, are a delight to know and work in perfect co-operation and friendliness – added to which their respect for the candidates is unbounded and their integrity beyond question. This is all quite apart from the social pleasure of staying and eating together leavened by a shared sense of exuberant humour and companionship. The organisation has been flawless under the guiding and tireless hand of Jill Rabenau, Executive Vice President and Competition Director of the Chopin-Gesellschaft in Darmstadt.

Competition Director of the Chopin-Gesellschaft in Darmstadt.

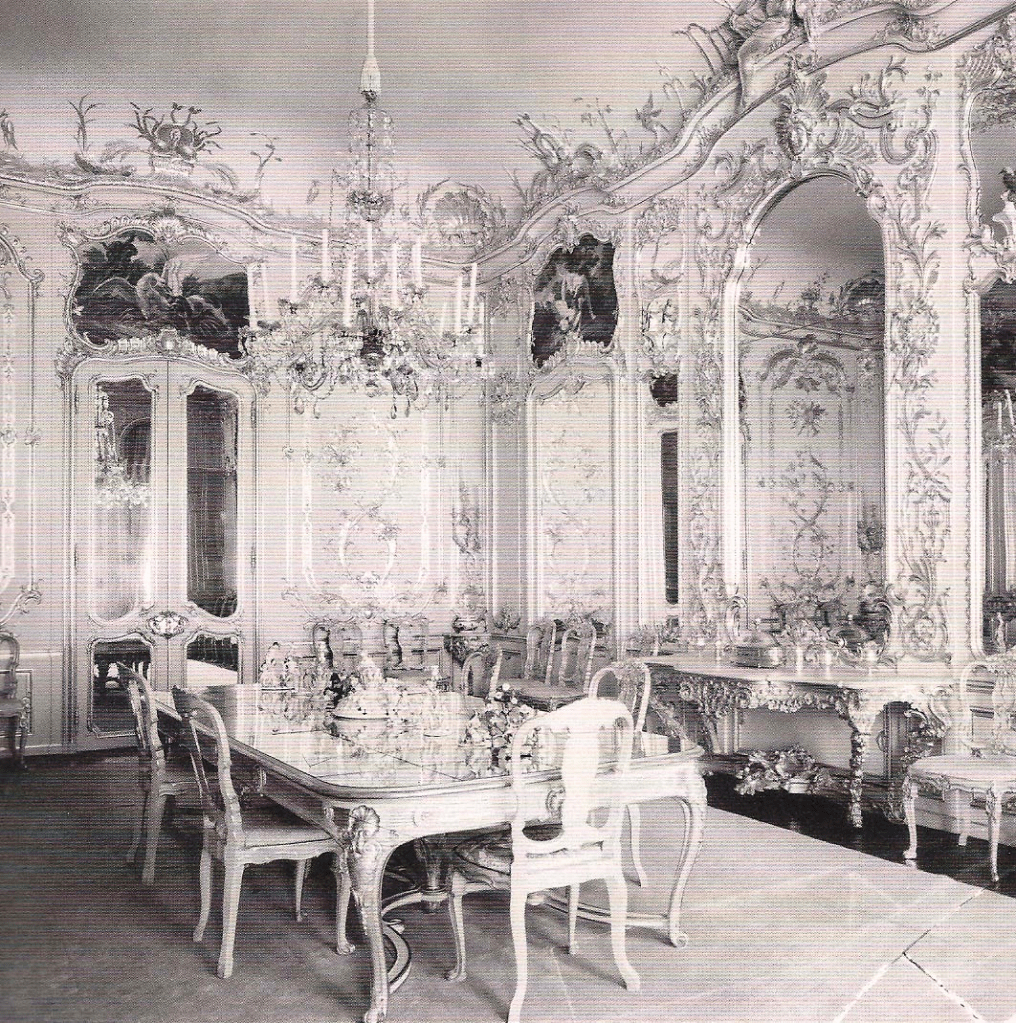

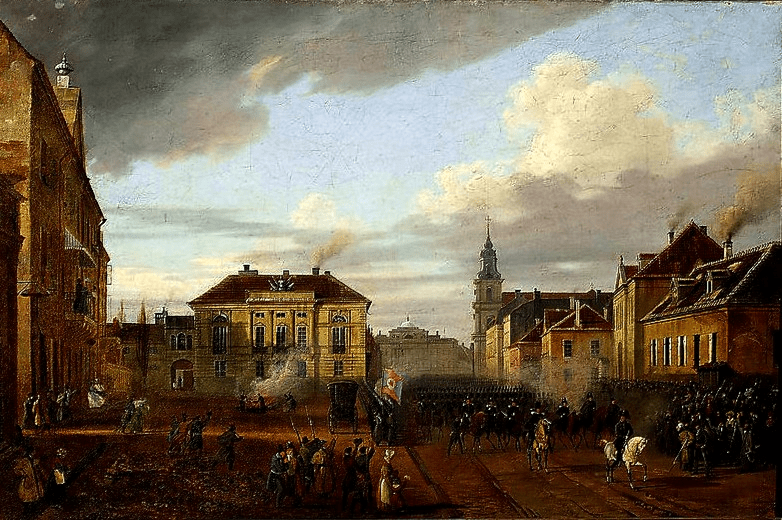

The competition takes place in the magnificent surroundings of the eighteenth century Orangery, a small palace built in 1721 by Remy de la Fosse in a baroque garden as winter quarters for orange trees. At present it is late autumn in Darmstadt but we are immersed in an Indian summer of sun, warmth and in addition are working in a glorious venue. The fine XII International Chopin Piano Competition is organized by the Chopin-Gesellschaft in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland E.V. who are celebrating their 50th anniversary.

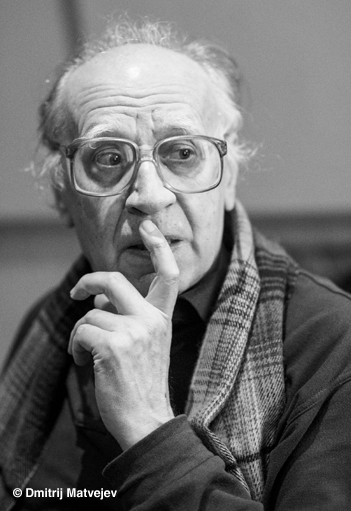

A reminder of the Jury members 2022

Kevin Kenner (USA, Chair)

Katarzyna Popowa-Zydroń (BUL/PL)

Dina Yoffe (LET)

Alexander Kobrin (USA)

Christopher Elton (GB)

Martin Kasik (CZ)

Sabine Simon (D)

Aleksandra Mikulska (PL / D) President of the Chopin-Gesellschaft

From Lt. Alexander Kobrin, Christopher Elton, Aleksandra Mikulska, Martin Kasik, Dina Yoffe, Sabine Simon,Katarzyna Popowa-Zydroń, Kevin Kenner

* * * * * * * * *

Reviews of Round III

The „Apollon Musagète Quartet“

Paweł Zalejski (violin)

Bartosz Zachłod (violin)

Piotr Skweres (Gennaro Gagliano

cello from 1741)

Słowomir Rozlach (double bass)

Piotr Szumieł (viola)

One of the world’s finest string quartets, the Apollon Musagète Quartet was founded by four Polish artists in 2006, in Vienna

All the candidates decided to play the

Chopin F minor concerto Op.21 with the Quintet

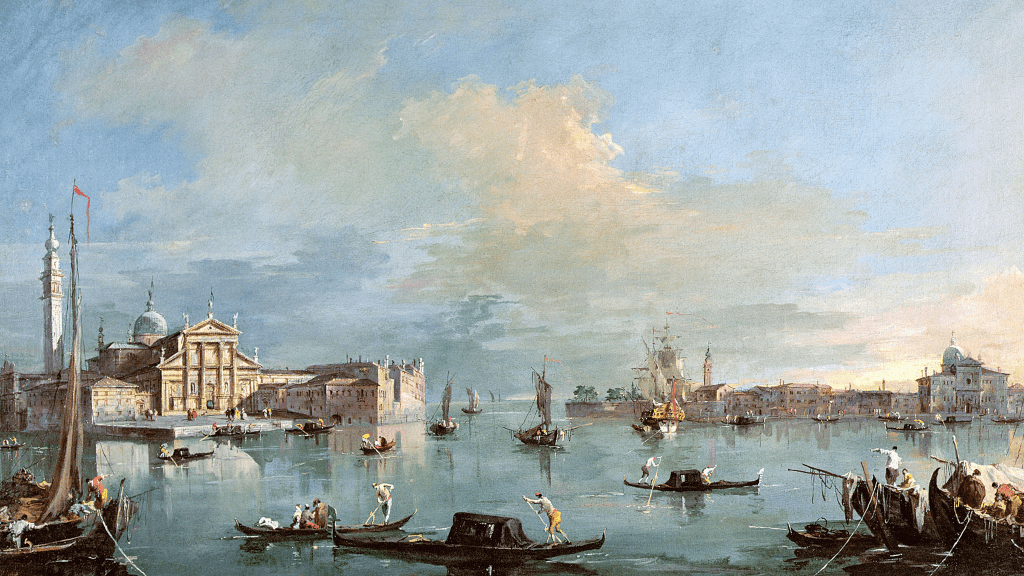

The return of squads of Polish army from Wierzbno to Warsaw (1831)

Marcin Zaleski (1796-1877)

First of all, a few notes on the Chopin Concerto in F-minor Op.21

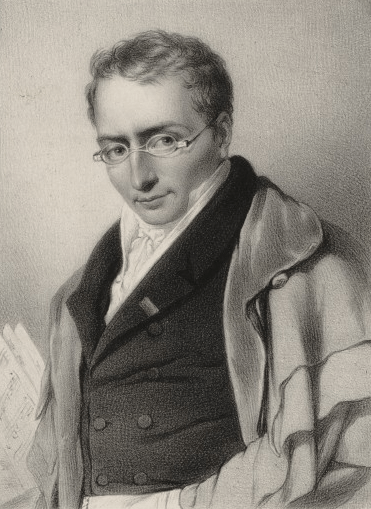

This concerto, the first Chopin wrote, follows the Mozart model and was directly influenced by the style brillante of Hummel, Kalkbrenner, Moscheles or Ries. Here in this early work, Chopin magically transforms the Classical into the Romantic style. The work itself was written 1829-30. As we all know by now, this concerto was inspired by Chopin’s infatuation, or was it youthful love, for the soprano Konstancja Gładkowska..Strangely it was published a few years later with a dedication to Delfina Potocka.

The first performance of his first piano concerto took place for a group of friends in the Chopin family drawing room at the Krasiński Palace on March 3, 1830. Karol Kurpiński, the Polish composer and pedagogue, conducted a chamber ensemble. One must remember that contemporary full orchestral forces were rare in the performance of concertos in Warsaw in the early 19th century.

The outer movements revolve like two glittering, enchanted planets around the moonlit, sublime melody of the central Larghetto movement, a nocturnal love song inspired by the soprano Konstancja Gładowska, Chopin’s object of distant sensual fascination whom he would soon leave in Poland. The well-known conflict of duty to one’s career and love. Liszt regarded the movement as ‘absolute perfection‘. Zdzisław Jachimecki, a Polish historian of music, composer and professor at the Jagiellonian University regarded it as ‘one of the most beautiful pages of erotic poetry of the nineteenth century.’

Versions for the concerto for chamber ensemble, such as this evening arranged by Kevin Kenner, were easier to assemble, less expensive and far more common. Our music world is comparatively overwhelmed with riches in terms full orchestra availability and such a multiplicity of recordings.

Fantee Jones

Maestoso

I was immediately struck by the intimate, chamber music impact of this concerto played on reduced forces. The richness of sound of this ensemble.

The opening Maestoso (quite a favourite stylistic indication in Chopin) was noble, even rhapsodic and considered with inner musical logic and coherence. Expressive and compositional details were placed as if under a magnifier and were never lost in the orchestral sound. In this movement there was a fine sense of youthful excitement and thoughtful keyboard exhibitionism, just as Hummel had laid the groundwork.

Jones seemed rather transformed tonight and I found more expressive than in her previous rounds. Quite passionate and committed without hectic tempi and dynamics. The solo violin counterpoint and devoted cello playing emerged as affecting, highly musical instrumental reductions of the orchestra. The fiorituras were perfect embellishments, seamlessly incorporated into the melodic lines. The L H counterpoint was inspiringly clear. A sense of youthful urgency pervaded the movement and Jones seemed emotionally transported by the music.

Larghetto

The opening on pure minimalist strings was intimately moving. The glorious melody rose over us like an aria or nocturne of love. Jones phrasing was sensitive and she created a seductive tone colour. There was much affecting cantabile and the fiorituras were graceful, elegant and grew as an organic part of the melody. I felt her playing of this movement rather a revelation. There were authentic feelings of yearning for an inaccessible love here, a sensitive sense of longing. Dynamic variations were moving and persuasive, particularly when the longing turns to the resentment of the unrequited lover but subsides again in nuances of pianissimo resignation to grim, rather sad reality. The pizzicato on the double bass was rather ominous and suggestive of hidden forces at work.In many ways you could say that the whole work revolves around this movement.

I always think of the sentiments contained in the 1820 poem by John Keats La Belle Dame Sans Merci when I hear this music with its passionate interjections

I met a lady in the meads,

Full beautiful—a faery’s child,

Her hair was long, her foot was light,

And her eyes were wild.

I made a garland for her head,

And bracelets too, and fragrant zone;

She looked at me as she did love,

And made sweet moan.

I set her on my pacing steed,

And nothing else saw all day long,

For sidelong would she bend, and sing

A faery’s song.

That final forty-note fioritura of longing played molto con delicatezza always carries me away into Chopin’s dreamy Romantic poetical world. Jones phrasing was most poetic.

Allegro vivace

In this ebullient movement she brought the sensual expression of the style brillante to life. There was energy, virtuosity and drive in this Rondo final movement, composed in the exuberant style of a kujawiak dance. She had already demonstrated this energy in previous rounds. There was an eruption of youthful style brillante which broke over us like the waves of the sea. It may even have been somewhat too up tempo. The col legno on the strings was most effective in expressiveness. The great Polish musicologist and pedagogue Mieczyław Tomaszewski writes of it:

A different kind of dance character – swashbuckling and truculent – is presented by the episodes, which are scored in a particularly interesting way. The first episode is bursting with energy. The second, played scherzando and rubato, brings a rustic aura. It is a cliché of merry-making in a country inn, or perhaps in front of a manor house, at a harvest festival, when the young Chopin danced till he dropped with the whole of the village. The striking of the strings with the stick of the bow, the pizzicato and the open fifths of the basses appear to show that Chopin preserved the atmosphere of those days in his memory.

How Chopin must have loved the bucolic nature of the Polish countryside and its music! The Chopin extension of the Hummel piano concerto was here fully realized. Melody and bravura figuration were wonderfully and authoritatively brought off with a balance of formal structure. At times, however, I did hope for more expressiveness as I feel her fine articulation needs to breathe more in her phrasing to create its full effect. This composition that lies between Mozart and the flowering of the style brillante was clearly created as were the gestures towards the concertos of Weber (following the splendid horn Cor de signal but tonight on the viola whose uniqueness always causes a smile). Fine technical delivery at the keyboard, tone and touch and a rather expressive conclusion of the dazzling coda concluded an excellent performance.

Da Jin Kim

Maestoso

I do encourage you to read of the genesis of the concerto in the previous review as I do not wish to repeat myself.

This rich and eloquent quintet began their reduced orchestral introduction with intense commitment. I have praised the actual refined and crystalline sound this pianist produced throughout the competition and it was similar here. This diminutive figure seemed to sculpt her phrases with rare musical insight. I found that her phrasing, rubato, tone, touch and use of silence resulted in a great poetic heightening effect. She was particularly sensitive to a musical phrase evolving with its own internal life. This is of significant importance in the creation of a true yet not superficial style brillante and bringing together the structure of this noble movement into a coherent whole. She does not rush but carefully builds the drama. The L.H. counterpoint was particularly attractive as she sings that melody at the keyboard. The only reservation I had was that the intensity of the communication of her ideas did not always wrap me with attention.

Larghetto

Her pianistic qualities and musical gifts were eminently suitable for this movement so imbued with the yearning of unfulfilled love. Delicate, graceful and intimate tone and touch in addition to an expanded time scale gave this movement rare qualities. There was a feeling of awaiting doom in the pizzicato on the double bass. Again, however, I felt my attention slipping away slightly during the rather slow tempo she adopted.

Allegro vivace

In this movement, whose Rondo has a very specific Polish element of dance, rhythm and drive, I felt an inability to project her involvement with these qualities. I felt that there was a bucolic and physical exuberance missing here in the rhythm although her tone and keyboard articulation remained brilliant. Not many pianists in the competition had a strong feeling for the Chopin period style, panache and élan of the Polish dance rhythms – mazurka, waltz and in this case, the kujawiak. May I just requote Tomaszewski on this movement:

A different kind of dance character – swashbuckling and truculent – is presented by the episodes, which are scored in a particularly interesting way. The first episode is bursting with energy. The second, played scherzando and rubato, brings a rustic aura. It is a cliché of merry-making in a country inn, or perhaps in front of a manor house, at a harvest festival, when the young Chopin danced till he dropped with the whole of the village. The striking of the strings with the stick of the bow, the pizzicato and the open fifths of the basses appear to show that Chopin preserved the atmosphere of those days in his memory.

This was a superbly refined performance of great aristocratic detachment which I appreciated greatly. However, I kept wondering about the absence of the bucolic and rather fun-filled nature of Chopin’ s youth – an actor, mimic, practical joker, satirist in print and sketches, writer of energetic style brillante compositions, playing dance music into the small hours, yearning for love….

Mateusz Tomica

I do encourage you to read of the genesis of the concerto in the previous review as I do not wish to repeat myself.

Maestoso

The opening was again in a noble and certainly Maestoso tempo with again a superb solo violin. I felt Tomica to be more ‘solid’, self-confident perhaps, in his phrasing and melodic line. I felt a degree of individuality I could not identify in the other candidates. There were a few blemishes and solecisms but he also he developed a close rapport, both emotive and musical, with the quintet (perhaps because he is Polish and so are they). This was a particularly noticeable comparison with the other candidates this evening who were more ‘distant’ from the quartet. I felt his whole approach was more dramatic, idiomatically ‘Polish’ and felt what Chopin remarked that ‘….in otherwise excellent performances, the Polish element was missing.’ Not in this case. There seemed to be far more driving energy than in the other performances.

Larghetto

Here I felt he could have been far more lyrical and poetic in his expressive range – something this movement requires, being as it is the focus of the entire concerto. However, he did nicely cultivate the fiorituras into meaningful emotionally expressive and ornamental sentiments within the melodic line. Period sensibility was at times charmingly in evidence. The whole movement was balanced and well structured.

Allegro vivace

Tomica developed an energetic and rather refreshingly muscular dance rhythm in the kujawiak. Perhaps his tone did not sparkle as brightly as the style brillante requires but it was foot-tappingly lively in essence. I felt they all had a heartfelt and physical appreciation of this dance rhythm which is so irresistible under the right fingers in this movement. Excellent driving energy. The entire ensemble play so well together, integrated as they all are by temperament including the composer. The Apollon Musagète Quartet with Słowomir Rozlach (double bass) were in fine form.

Wojtech Trubac

For the interpretation of concerto, do read my historical and cultural notes above for Festee Jones.

Maestoso

After the always moving introduction by the Quintet, I felt Trubac entered at just the right noble, Maestoso tempo that Chopin may have had in mind. I felt his piano tone on the Kawai blended well with the rather mahogany sound of this ensemble. I felt he created well-judged dynamic variations as the emotion and passion heightened, following the quintet and communicating well with them. As I listened I could not help reflecting on the extraordinary skill of Chopin to offer the audience exactly what they wanted and still want musically. A painting of the emotional landscape of a young man. I felt Trubec was familiar and in control of the piano part with the lyricism well balanced with bravura playing. He had a strong sense of structure and the style brillante left nothing to be desired.

Larghetto

I felt his approach to be sensitive, lyrical and poetic in feeling for this seductive melody. I found the simplicity of his playing of this movement most affecting, ‘simplicity’ being a quality Chopin admired above almost all others. Musically his fine legato allowed the melodic line to move forward naturally, sketching an eloquent aesthetic arc. His tone and touch were never harsh or rough and I admired his finely cultivated poignant and expressive arabesques when introducing the fiorituras. They were often caressed with love into ardent gestures. The counterpoint melody on the cello (a favourite instrument of Chopin) was so moving. The doubts that beset one when in love rose inexorably. The string tremolos of emotional agitation, above which the piano sings, were most affecting. This focal movement of the concerto was most satisfying for me.

Allegro vivace

This fiendishly difficult, long Rondo movement emerged with Trubac as a joyful kujawiak dance where the phrases blended seamlessly into one another. Again the col legno on the strings was touching with such reduced forces. The hunting cor de signal transferred from a solo horn to the viola was quite successful. I liked very much his style brillante and optimistic rhythms that pressed forward with an impetus all their own. The audience clearly admired this rhythmic drive. The Chopin aesthetic comes naturally to Trubac and I admired his expressive variation in dynamics.

Zvjezdan Vojvodic

Maestoso

Fine, astonishing, intense but naturally still youthful playing as one might expect from a lad of nineteen. I found his communication of inner detail and transparency ‘inside’ the piece remarkable as was his L.H. counterpoint. His execution of this complex movement tended to be uneven on occasion and small errors from nervousness and inexperience crept in, but this was an astonishing demonstration of musical and pianistic preciosity. Vojvodic is only slightly younger than Chopin’s age when he wrote the work. Here we have a remarkable developing talent who has already been rewarded with a place in the finalists line-up.

Larghetto

I found it surprising that such a young talent has such a poetic insight into this movement, but then again Chopin wrote it when he was much the same age. I noticed also that Vojvodic had an excellent and quite emotional connection with the chamber musicians. The eloquent fiorituras were touched with romantic yearning and the variation in dynamics and dynamic contrast built up a coherent picture of the romance and sentiments that Chopin intended to convey.

Allegro vivace

I was again astonished at this precocious talent and his command of the keyboard in this long challenging Rondo. He is certainly on the way to developing an individual voice, even if a few errors crept into this energetic, demanding movement. I felt he possessed a perceptive understanding of the musical gestures and phrases that imbue this Allegro vivace with its irresistible momentum. He seemed rather possessed by the music at times and already has a command of the style brillante with his digital facility and strength. As long as he can control and moderate the impatience of youth and work consistently, allowing his talents to grow organically and unforced in time as in Nature, all will be well to outstanding!

Andrey Zenin

Maestoso

From the beginning of Round I I felt this pianist was possessed of an authority in his playing most of the others had not yet achieved. This became evident too in Round II in the Boléro and the Scherzo in B flat minor Op. 31.

With this fine and passionately committed quartet he also made a significant musical impact in the concerto. Perhaps understandable nervousness caused his first entry to be slightly early but this was soon forgotten as he began to present Chopin as a ‘grand maître’ of the instrument. His high virtuoso, noble and majestic style of presentation does suit this opening Maestoso movement well. He maintained a strong internal pulse throughout but I felt his expressiveness occasionally wanting in the grand flourishes of this passionate writing. He has great authority in his playing.

Larghetto

He was not tempted, as many pianists are, to sentimentalize the glorious love theme of this movement. His phrasing brought occasional gestures of sweet tenderness to the Larghetto. This made the eruption of the mood change all the more disturbing and appropriately violent, imbued as it is with that untranslatable Polish emotion of żal. The resonant double bass gave an under-carpet of potential doom to the sunny, untroubled lyricism of young love winging above the turmoil of ‘reality’ which I found quite unsettling.

The ensemble clearly felt a rather close connection with his phrasing and they worked together in quite a symbiotic relationship. The transparency of Chopin’s writing is so clear with the smaller ensemble (the brilliant cello ‘playing’ a number of the transcribed orchestral instruments). The polyphony and counterpoint evolve into a pianistic Adagio mood that may well have moved Mozart.

Allegro vivace

This movement was played with great style and impressive virtuosity but for me missed some of the essential qualities of the style brillante. This style was characterized by lightness, delicacy, charm, sonority, purity, precision and a rippling execution resembling pearls. Although brilliantly played, these qualities were not present with Zenin in this Rondo for me. Naturally the movement can be played in this accomplished virtuoso and effective manner, if this is your view of Chopin. As I have said many times, everyone has their ‘own Chopin’ and will defend it to the death. I can think of no other composer than perhaps Bach that elicits such hotly defended views! There was powerful, authoritative, irresistible forward impetus here and a feeling of ‘pressing on’ but the expressive gestures were somewhat limited in scope. Overall, a triumphal and well formed interpretation of the concerto that was most impressive.

Round II

Reviews of Round II Candidates

Anton Drozd – Ukraine

a) Polonaise-Fantaisie A flat-major op. 61

Again I make no apology for repeating my introduction to this and other works as such background facts do not change although the interpretative approach by various pianists is always completely different. Once mentioned I shall not repeat the genesis of a work when it appears again in the competition.

The Polonaise-Fantaisie contains all the troubled emotion and desire for strength in the face of the multiple adversities that beset the composer at this late stage in his life. This work, the first in the so-called ‘late style’ of the composer, was written during a period of great suffering and unhappiness. He laboured over its composition. What emerged is one of his most complex of his works both pianistically and emotionally. Chopin produced many sketches for the Polonaise-Fantaisie and wrestled with the title. He had written: ‘I’d like to finish something that I don’t yet know what to call’. This uncertainty indicates surely he was embarking on a journey of compositional exploration along untrodden paths. Even Bartok one hundred years later was shocked at its revolutionary nature. The work is an extraordinary mélange of genres and styles in a type of inspired improvisation that yet maintains a magical absolute musical coherence and logic. He completed it in August 1846.

The opening tempo is marked maestoso (as with his two concerti)which indicates ‘with dignity and pride’. I was impressed with Drozd’s deliberate phrasing of the opening, the dreamlike, poetic fantasy of his opening phrases of considered expressive emotion contrasted with the passionate expression which immediately sets the atmosphere. I felt the piece was being searched for and discovered as a type of improvisation which I feel it needs. The invention fluctuates as if with the irregular circulation of the heart and the blood. Some passages were rather rushed in their urgency and the considered musical narrative was at times uneven.

However, I felt Drozd had touched many polyphonic and normally concealed expressive structures and was moved as ever by this remarkable music. His bravura playing suffered technical limitations and solecisms. There is much rich counterpoint and polyphony to be explored here (of which Chopin was one of the greatest masters since Bach). This work also conveys a strong sense of żal, a Polish word in this context meaning melancholic regret leading to a mixture of passionate resistance, resentment and anger in the face of unavoidable fate. Yes, a complex work for a young man to master, written when Chopin was moving towards the cold embrace of death.

b) Impromptu G sharp major op. 51

I feel this work carries an atmosphere of elegance, refinement and the grace of another age, possibly that of the Parisian salons Chopin inhabited – yet is not in the slightest degree superficial. Perhaps Drozd could have introduced more of a feeling of spontaneity and shifting moods (albeit of a restrained type) and even more invention ‘on the spot’ (the choice of title ‘Impromptu’ surely indicates such an aspect of interpretation).

André Gide, who was also a fine pianist as well as a writer, wrote affectingly of the impromptus in his Notes on Chopin :

‘What is most exquisite and most individual in Chopin’s art, wherein it differs most wonderfully from all others, I see in just that non-interruption of the phrase; the insensible, the imperceptible gliding from one melodic proposition to another, which leaves or gives to a number of his compositions the fluid appearance of streams.’

I liked the whimsical feeling Drozd gave to the work and the improvisational atmosphere that overlaid his conception.

c) Rondo E flat major op. 16

The essential nature of the style brilliant of which the Rondo is representative of Chopin’s early Varsovian style, seems rather a mystery to modern pianists outside of those living in Poland. Perhaps I am hopelessly wrong. The style involves a bright light touch and glistening tone, varied shimmering colours, supreme clarity of articulation, in fact much like what was referred to in French as the renowned jeu perlé. There are also vital expressive elements of charm, grace, taste and elegance.

One must not forget that Chopin astonished Vienna by his pianism but perhaps even more by the elegance of his princely appearance. The limpid, untroubled and joyful nature of the early polonaises, mazurkas, rondos, sets of variations on Polish themes and piano concertos were written in this virtuosic style brillante fashionable in Warsaw. This style was characterized by lightness, delicacy, charm, sonority, purity, precision and a rippling execution resembling pearls. These works could only have been composed in a state of happiness and youthful ‘sweet sorrows’ living in his native land.

However this interpretation was not entirely the style brillante as I understand it. The many fiorituras were not always presented as decorative Venetian lace, the hand and touch rather too focused on bravura than cultured refinement, charm and affected elegance. Even though brilliantly performed, the work was somewhat stylistically inaccurate for me. In this work by Chopin the young man, I felt we needed more of the grace, elegance and refinement that lies within this style brillante piece that I feel has no deeper intention than to entertain the listener with beauty in the most civilized and sophisticated manner we can imagine.

d) Waltz C sharp minor op. 64/2

I found this familiar piece approached in a particularly attractive and unique manner at a slow tempo. It appeared veiled as if in a remembered dream in a ballroom that honoured it as a guest.

e) Polonaise G flat major op. posth.

‘Chopinek’ composed his first Polonaise at the age of seven. The nineteenth-century poet and critic Kazimierz Brodziński defined the dance:

The polonaise breathes and paints the whole national character; the music of this dance, while admitting much art, combines something martial with a sweetness marked by the simplicity of manners of an agricultural people . . . Our fathers danced it with a marvellous ability and a gravity full of nobleness; the dancer, making gliding steps with energy, but without skips, and caressing his moustache, varied his movements by the position of his sabre, of his cap, and of his tucked-up coat sleeves, distinctive signs of a free man and a warlike citizen.

A clear distinction must be made between these early polonaises which were far more of a dance genre than an angry, militaristic atmosphere of resentment, vengefulness, regret and that untranslatable Polish term żal so applicable to much of Chopin’s later music. Drozd gave us a delightful energetic statement, but the impulsive, youthful nationalism of the work was slightly rushed at times.

Balazs Fazekas – Slovakia

a) Variations brillantes B flat major op. 12

In the 1830s, in Paris, Chopin returned to variations. In 1833 he composed Variations in B flat major, Op. 12, on the theme ‘Je vends des Scapulaires’ from the Hérold/Halévy opera Ludovic. This work, elegant, sparkling and of shallow expression, is regarded as a further nod in the direction of the style brillante, this time in the ‘Parisian’ style, bringing little to his oeuvre.

His tone was rounded and clear and his touch light, stylish and refined. Excellent qualities for the Chopinesque style brillante in these Variations.

b) Polonaise G sharp minor op. posth.

I found his approach to this piece rather charming with his bright tone and elegant touch. In this rarely performed work. the rhythm he maintained was infective and gave rise to the urge to dance.

c) Impromptu A flat major op. 29

I found his presentation of the work slightly rushed but perfectly acceptable in terms of a feeling of improvised spontaneity.

d) Fantaisie-Impromptu C sharp minor op.66

The romantic emotions inseparable from this familiar work were held back for some reason especially in the lyrical central cantabile song.

e) Scherzo B minor op. 20

A strong and convincing declamatory opening. Frederick Niecks quotes Robert Schumann who wrote of the Chopin Scherzos (the Italian word scherzo meaning ‘joke’) ‘How is ‘gravity’ to clothe itself if ‘jest’ goes about in dark veils?’. I found this account fittingly mercurial with good L H counterpoint and transparent polyphony. The lyrical section was finely legato and had much affecting phrasing. There was an eruption of żal (an untranslatable concept used often in relation to Chopin – moments passionately lyrical, then introspective, then expressing that characteristic Polish bitterness, passion and emotionally-laden disturbance of the psyche – melancholic regret leading to a mixture of passionate resistance, resentment and anger in the face of unavoidable fate)

Adam Gozdziewski – Poland

a) Sonata in C minor op. 4 (Movments I & II)

The decision of the organizers in favour of the first sonata in C minor forced them to exclude from the repertoire the two famous sonatas in B minor and B-flat minor due to time limitations. This decision was not taken lightly.

This work was written by Fryderyk Chopin in 1828. It was written during Chopin’s time as a student with Józef Elsner, to whom the sonata is dedicated. Despite having a low opus number, the sonata was not published until 1851 by Tobias Haslinger in Vienna, two years after Chopin’s death. This work is unaccountably for me considered to be a less sophisticated work. It is considered less musically advanced than the later sonatas, and is thus far less frequently performed and recorded.

The sonata has four movements of which we heard the first two. I very much enjoyed hearing these two movements. Chopin only ever wrote one Minuet. Gozdziewski made it formally quite acceptable and respectable to be a work in the repertoire.

Allegro maestoso

Menuetto

Larghetto

Finale: Presto

b) Polonaise B flat major op. 71/2

This work written in 1828 rests on the cusp of change. It shows Chopin beginning to introduce personal moods and emotions into his work and move away from conventional expressions in the shackles of previous forms and genres. This Polonaise seems to be one of the documents of an imminent breakthrough. It was composed in the virtuosic style brillante. Really it is a piece of chamber music for an intimate room. As Frederick Niecks noted, in Chopin’s music from that time ‘The bravura character is still prominent, but, instead of ruling supreme, it becomes in every successive work more and more subordinate to thought and emotion’. This work admirably reconciles the conventional with the original, the coquetry of the salons with the approaching Romantic watershed (Tomaszewski)

Gozdziewski gave an excellent account of the work even if lacking slightly in finesse and sense of period style.

c) Impromptu G flat major op. 51

A string sense of improvisation was obvious here but I still felt it was not quite spontaneous enough to contribute the feeling of ‘on the spot’ invention. These are not grand serious works but lighter salon or chamber pieces to uplift the spirits – and none the worse for that.

d) Barcarolle F sharp major op. 60. It was a fine performance but without great personal distinction and could have been a little more spontaneous as the moods fluctuate and take hold on this romantic excursion across the lagoon or bay.

Fantee Jones – USA/ Taiwan

a) Ballade A flat major op. 47

In the music of the A flat major Ballade, which unfolds a dizzying array of events, attempts have been made to discern and identify the separate motifs, characters and moods. Two possible sources of inspiration have been inferred. Interestingly, they can be reduced to a common, supremely Romantic, denominator. Schumann was captivated by the very ‘breath of poetry’ emanating from this Ballade. Niecks heard in it ‘a quiver of excitement’. ‘Insinuation and persuasion cannot be more irresistible,’ he wrote, ‘grace and affection more seductive’. In the opinion of Jan Kleczyński, it is the third (not the second) Ballade that is ‘evidently inspired by Adam Mickiewicz’s Undine. That passionate theme is in the spirit of the song “Rusalka.” The ending vividly depicts the ultimate drowning, in some abyss, of the fated youth ‘in question’.

A different source is referred to by Zygmunt Noskowski: ‘Those close and contemporary to Chopin’, he wrote in 1902, ‘maintained that the Ballade in A flat major was supposed to represent Heine’s tale of the Lorelei – a supposition that may well be credited when one listens attentively to that wonderful rolling melody, full of charm, alluring and coquettish. Such was surely the song of the enchantress on the banks of the River Rhine’, ends Noskowski, ‘lying in wait for an unwary sailor – a sailor who, bewitched by the seductress’s song, perishes in the river’s treacherous waters’.

Penetrating the expressive core of the Chopin Ballades requires an understanding of the influence of a generalized view of the literary, musical and operatic balladic genres of the time. In the structure there are parallels with sonata form but Chopin basically invented an entirely new musical material. I have always felt it helpful to consider the Chopin Ballades as miniature operas being played out in absolute music, forever exercising one’s musical imagination. The work contains some of the most magical passages in Chopin, some of the greatest moments of passionate fervour culminating in other periods of shattering climatic tension.

This was a fine performance of the Chopin Ballade in A flat major Op. 47 with ‘narrative’ musical force. In Round 1 her performance was quite satisfying apart from the Études. Pianistically here, there could have been more expression and dynamic variation.

b) Tarantelle A flat major op. 43

‘I hope I’ll not write anything worse in a hurry’ – Chopin’s rather unflattering assessment of the Tarantella. Shortly after arriving in Nohant, Chopin wrote to Julian Fontana with the manuscript of the Tarantella (to be copied): ‘Take a look at the Recueil of Rossini songs […] where the Tarantella (en la) appears. I don’t know if it was written in 6/8 or 12/8. Both versions are in use, but I’d prefer it to be like the Rossini’

It did have some feeling of frenzy from the growing effects of the poisonous tarantula bite but for me it lacked the characteristic joyfulness and gaiety of the Italian dance, the rhythm and tempo seemed incorrect. I thought Jones could have given us a more convincing rhythmic account of the victim of a poisonous spider bite (by the Tarantula) and the growth of the insidious, destructive chemical circulating in the blood. Traditionally the victim became well and truly beside himself, increasingly and madly so by the triumphant conclusion.

d) Polonaise E flat minor op. 26/2

I found the haunting, deeply expressive ominous beginning followed by a burst of raw energy developed into an exciting but rather uneven pattern where the tensions and relaxations of passion vital to the work were not sufficiently cultivated. The Italian monographer Ippolito Valetta called the work a ‘revolt against destiny’. The mood swings throughout the work required a variety of colour and articulation. Strength emerged from depression and despair in this, the darkest of all Chopin polonaises. She could have made a great deal more of this remarkably dark work.

However, I am not Polish and always feel my Western cultural background insufficient in plumbing the true nature of Polish suffering. It is hard to comment seriously on the existential and historical significance of the Chopin polonaise as a distillation of Polish nineteenth century anguish. I can but try….The eminent Polish philologist Tadeusz Zieliński (1859-1944) ventured a thought-provoking assessment: ‘The Polonaise in E flat minor is one of the most beautiful – or perhaps the most beautiful – of Chopin’s polonaises’. Certainly it is one of the most emotionally moving.

c) Sonata C minor op. 4

Jones courageously decided to play the entire sonata which gave us a more balanced view of this rather unpopular work. She adopted a rather serious view of the piece where it may benefit from an approach that concentrates more on the period atmosphere. The opening Allegro maestoso (in C minor) is cast in sonata form. I much liked the charm and pleasant simplicity of the Menuetto and Trio and the Larghetto which also possessed an uncomplicated attractiveness. The Presto was the most successful from the compositional point of view, The final movement is undoubtedly the most successful and Chopinesque movement of them all. Jones gave it fire, virtuosity, inventiveness and passion although I felt her approach rather unvaried dynamically as it hurtled forward.

Da Jin Kim – South Korea

a) Rondo E flat major op. 16

The first aspect of her playing that I noticed was the crystalline tone and refined touch. It seems to be a cultivated speciality of South Korean pianists. There is an alluring charm and elegance in her playing in the stye brillante. Her approach would have been even more impressive if she breathed the phrases more expansively and expressively. This would give the listener time to react emotionally, to decode what she is saying within the piece and convert the feeling into meaningful emotion. All too often the pianist is so familiar with a work through practice they forget the listener is not as familiar with the perhaps inner polyphonic detail and has to actually follow what is evolving musically. This is not always possible at rapid tempi. Kim showed great energy and exuberance with an excellent sense of structure.

b) Polonaise in G flat major op. posth

Here Kim attractively highlighted the melody. I felt a charming division into sections based on the style of the musical writing. She introduced a great deal of creative dynamic variation.

c) Ballade F minor op. 52

The narrative began well with the ‘balladeer’ opening the musical narrative. She produced many golden cantabile expressive sections and possessed an excellent sense of structure. I found this a most impressive recital that was not drowning me in dynamic sound. She has a far more accurate sense of period style that many in the competition. The inner workings of the work in terms of polyphony and harmonic transitional detail were often transparent. Again however, I simply wish that there was a little more discipline of tempo instead of being carried away by virtuosity and its physical excitements and satisfactions. A question of age? In Round 1 I wrote in my notes of similar feelings of sensitivity as above and my reservations concerning expression being sacrificed on the altar of virtuosity in the Études.

d) Impromptu G flat major op. 51

I found this wonderfully light in mood as she presented this blithe and untroubled work

Haeun Kim – South Korea

a) Ballade F major op. 38

Again there was this captivating, crystalline sound from the instrument. Kim opened the work with captivating childish innocence and adorable simplicity of melody. This was followed by explosive passions of the grim reality of war or love, the suffering, the feast of the tigers of experience followed a naive lack of knowledge of the world. I have always felt this work to be traversing the emotional landscape of a broken love affair. Technically in terms of articulation, tone and touch his performance was formidably impressive with occasional lapses of deeper expressiveness as dynamic exaggerations tended to rear their ugly heads. I felt the dynamic contrasts could have been moderated.

b) 3 Nouvelles Etudes Although played ‘perfectly’ I always feel such glorious melodies should be ‘dwelt upon’ or played with particular expression and attractiveness and as they are so full of guileless charm.

c) Polonaise B flat major op. 71/2

I dealt with the detailed genesis of this work in the Adam Gozdziewski review above if you are curious. The shadows of Polish nationalism hover over the work even suffusing its charming melody. Kim played the work with an ingratiating tone and seductive touch,attractive phrasing gleaned from her active imagination and more than a little style brillante. Kim presented us with a convincing polonaise. She pianist has an enviable natural fluency at the instrument.

d) Rondo E flat major op. 16

I can do no better than quote in full the fascinating historical note on this Rondo written by the great Polish musicologist Mieczysław Tomaszewski.

” The Rondo in E flat major, Op. 16 was possibly composed during a beautiful summer spent at Côteau, and it was published in the autumn of 1833 with an unusually long dedication: ‘dedié à son élève Mademoiselle Caroline Hartmann par…’ (‘dedicated to his pupil Miss Caroline Hartmann by…’). This work is pure virtuosic display.

It scurries by in a single breath – allegro vivace, as befits a rondo. It wavers between risoluto and dolce, falling here and there into rubato, brillante and leggiero. In the opinion of Jachimecki, who is rather critical of this work, ‘the themes slide smoothly over the keyboard, without disturbing the varnish…’ The refrain brings a distant echo of a krakowiak – of the ballroom, rather than country tavern, variety.

The Rondo in E flat major – like the Variations on a theme from the opera Ludovic and the Grand Duo Concertant on themes from Robert le diable – bears testimony to a time that might be called a period of adaptation. The young pianist from Warsaw is trying to find his place in Paris – a city that has bewildered and partly also enslaved him. ‘For a while’, as he confessed to Elsner – he wanted to put aside ‘loftier artistic vistas’ and he wrote ‘I am forced to think about forging a path for myself as a pianist’. As a pianist composing music that was in vogue, like that being composed by all those around him, such as Kalkbrenner, Herz, Moscheles and Thalberg – music intended for the Parisian salons. This sparkling Rondo, which dazzles with its pianistic virtuosity, was composed in that Parisian bon goût.“

Kim, befitting the work, played in a spectacular, sparkling fashion with an attractive rhythm. She did however slightly rush over the affecting harmonic transitions (a common fault among most candidates in this competition). I dearly wanted to be taken ‘inside’ the work. Her performance was full of attractive excitement and winning impulsiveness.

Ballade in G minor op. 23

Penetrating the expressive core of the Chopin Ballades requires an understanding of the influence of a generalized view of the literary, musical and operatic balladic genres of the time. In the structure there are parallels with sonata form but Chopin basically invented an entirely new musical material. I have always felt it helpful to consider the Chopin Ballades as miniature operas being played out in absolute music, forever exercising one’s musical imagination.

‘I have received from Chopin a Ballade’, Schumann informed his friend Heinrich Dorn in the autumn of 1836. ‘It seems to me to be the work closest to his genius (though not the most brilliant). I told him that of everything he has created thus far it appeals to my heart the most. After a lengthy silence, Chopin replied with emphasis: “I am glad, because I too like it the best, it is my dearest work”.’

The great Polish musicologist Mieczysław Tomaszewski paints the background to this work best:

” It was during those two years that what was original, individual and distinctive in Chopin spoke through his music with great urgency and violence, expressing the composer’s inner world spontaneously and without constraint – a world of real experiences and traumas, sentimental memories and dreams, romantic notions and fancies. Life did not spare him such experiences and traumas in those years, be it in the sphere of patriotic or of intimate feelings. […] For everyone, the ballad was an epic work, in which what had been rejected in Classical high poetry now came to the fore: a world of extraordinary, inexplicable, mysterious, fantastical and irrational events inspired by the popular imagination.

In Romantic poetry, the ballad became a ‘programmatic’ genre. It was here that the real met the surreal. Mickiewicz gave his own definition: ‘The ballad is a tale spun from the incidents of everyday (that is, real) life or from chivalrous stories, animated by the strangeness of the Romantic world, sung in a melancholy tone, in a serious style, simple and natural in its expressions’. And there is no doubt that in creating the first of his piano ballades, Chopin allowed himself to be inspired by just such a vision of this highly Romantic genre. What he produced was an epic work telling of something that once occurred, ‘animated by strangeness’, suffused with a ‘melancholy tone’, couched in a serious style, expressed in a natural way, and so closer to an instrumental song than to an elaborate aria. “

Kim gave the work a fine narrative opening, however I did not feel it evolved episodically in musically felt scenes. It engaged me pianistically but only on a high virtuosic level, very satisfying in its way but not realizing the full poetic and associative potential of the work.

Uram Kim – South Korea

c) Variations brillantes B flat major op. 12

In the 1830s, in Paris, Chopin returned to variations. In 1833 he composed Variations in B flat major, Op. 12, on the theme ‘Je vends des Scapulaires’ from the Hérold/Halévy opera Ludovic. This work, elegant, sparkling and of shallow expression, is regarded as a further nod in the direction of the style brillante, this time in the ‘Parisian’ style, bringing little to his oeuvre.

Kim gave the Variations an ostentatious, theatrical opening. However, I found his pianism, although communicative and brilliant, rather heavy at times. Some of these variations are not intended to be so pedantic and loud. He has natural and illuminating musical phrasing which gave us a highly entertaining style brillante work of Chopin the young man.

b) Boléro op. 19

I enjoyed this fine performance of one of my favourite Chopin compositions immensely. Kim had an excellent feel for this dance although the opening was rather savage! He gave the work a fine improvised feel with excellent sprung rhythm. His tone and touch suited the work perfectly. He brought out the ‘jazz’ element of this piece, toning down the virtuoso display.

The boléro was originally a lively Spanish dance in triple metre originating in the 18th century and popular in the 19th. It bears a resemblance to the polonaise which is perhaps why Chopin wrote one.

d) Polonaise G sharp minor op. posth.

Overall Kim played more sensitively than in Round 1 but the beginning was again too impulsive. This style brillante early work benefitted from the particular pianistic skills this Korean brings to the instrument. For reasons explained elsewhere I am not partial to the ‘fioritura streaks’. In the recent Julian Barnes novel The Man in the Red Coat, Count Robert de Montesquiou has a pet tortoise that expires after being painted gold and studded with jewels, and its carapace becomes “its metallic and gemmate tomb.” I sometimes feel an analogous case in pianism where glittering playing precludes exploration of any deeper content of a piano composition.

e) Scherzo E major op. 54

This image of the glittering turtle shell also took hold of me in the Scherzo. The internal irrationality and neurotic dislocation evident within this piece rather escaped Kim as he seemed more attracted to the surface virtuosity of the phrases rather than the complex living interior of the piece that the surface was concealing. The dynamic contrast seemed too extreme for me. The polyphony was obscured and much inner detail as the work became simply and only pianistic and so the living interior expired. Chopin seduces one inside his work but one must become sensitive to his gestures.

Leonhard Krahforst – Poland

a) 3 Nouvelles Etudes

He applied a fine legato and skilful pedalling to produce a highly expressive account of these charming pieces. The blithe good humour and happiness with the affecting melodies was much in evidence.

b) Ballade A flat major op. 47

I gave the genesis of this work in the Fantee Jones review above if you are further interested.

Krahorst gave this an unusual and low key narrative without hysteria which I much enjoyed. I was drawn into his narrative as one is with any outstandingly skilful teller of tales to which he added many varied dynamics. There was fine attention to tensions and relaxations within the work. His arcs of emotional disturbance were disciplined and controlled.

c) Polonaise B flat major op. 71/2

Again the genesis of this work is within the Adam Gozdziewski review above.

Krahforst gave a civilized and graceful yet strong performance of this work. The ornamentation was controlled and attractive in scale. His tone and touch were highly cultivated. He highlighted such a simple, poignant melody which I found most affecting. Overall this was a performance with great finesse with nothing overwrought, always the irresistible temptation to exaggerate that young pianists face with Chopin.

d) Variations sur “Là ci darem la mano” B flat major op. 2

(National Trust, Fenton House)

Then the youthful Chopin Variations in B-flat major on ‘La ci darem la mano’ from Don Giovanni. Chopin was seventeen when he composed this style brillante virtuoso work for piano and orchestra. The influence of Hummel is clear (Chopin greatly admired his playing as did the rest of Europe! His joyful, untroubled music is still undeservedly neglected. Audiences were said to stand on their chairs to see how Hummel accomplished his trills. Now that does not happen today!) The piano was an evolving instrument and each new development created great excitement among composers of the day. Chopin as a youth haunted the Polish piano factory of Fryderyk Buchholtzof in the role of what we might term an ‘early adopter’.

Chopin composed the ‘Là ci darem’ Variations in 1827. As a student of the Main School of Music, he had received from Elsner another compositional task: to write a set of variations for piano with orchestral accompaniment. As his theme, he chose the famous duet between Zerlina and Don Giovanni from the first act of Mozart’s opera Il dissoluto punito, ossia il Don Giovanni. In this opera overwhelming power and faultless seduction meet maidenly naivety and barely controlled fascination. (Tomaszewski)

In his famous first review of Chopin’s variations on Mozart’s ‘Là ci darem la mano’, Schumann gives us a striking description:

“Eusebius quietly opened the door the other day. You know the ironic smile on his pale face, with which he invites attention. I was sitting at the piano with Florestan. As you know, he is one of those rare musical personalities who seem to anticipate everything that is new, extraordinary, and meant for the future. But today he was in for a surprise. Eusebius showed us a piece of music and exclaimed: ‘Hats off, gentlemen, a genius! Eusebius laid a piece of music on the piano rack. […] Chopin – I have never heard the name – who can he be? […] every measure betrays his genius!’”

Chopin’s ‘Là ci darem’ variations are classical in form with an introduction, theme, five variations and finale. They are a marvellous example of the style brillante and clearly influenced by Hummel and Moscheles.

It is well-known Chopin was obsessed with opera all his life, a fascination that began early. Krahforst applied phrasing that was uncannily as if the aria was being sung with vocal intonation and alluring and charming cantabile. Clara Wieck loved this work and performed it often making it popular in Germany. Her notorious father, who had forbidden her marriage to Robert Schumann, wrote perceptively and rather ironically of this work: ‘In his Variations, Chopin brought out all the wildness and impertinence of the Don’s life and deeds, filled with danger and amorous adventures. And he did so in the most bold and brilliant way’.

Krahforst began with a thoughtful introduction. I feel this pianist has deep musicality, true musical fluent speech as the piece moved forward. He was slightly lacking in projected energy at times and the work began to sound drawn out despite the glittering style brillante execution. I felt also each variation could have been delineated more clearly from the next. I felt, although he began well, he slowly lost my attention as the piece progressed over such a long duration and the progression of the structure remained somewhat unclear.

Yuna Nakagawa – Japan

a) Polonaise C Minor op. 40/2 (1838-39)

The polonaise is believed to have been composed in the dark atmosphere of the Carthusian monastery in Valldemossa. It would be difficult to find an alternative to the definition advanced by the writer, historian and musicologist Ferdynand Hoesick who wrote of the ‘gloomy mood’ that emanates from this music, of its melancholy and ‘tragic loftiness’.

Dedicated to Julian Fontana, Chopin wrote: ‘You have an answer to your honest and genuine letter in the second Polonaise. It’s not my fault that I’m like that poisonous mushroom […] I know I’ve been of no use to anyone – but then I’ve been of precious little use to myself’.

Nakagawa rather rushed this great polonaise and did not successfully build a structure. The Trio, a tragic and sublime, nostalgic sung cantilena rather fell apart. Cruel and brutal destiny hovers over it and reality erupts once again to destroy the dream.

b) Rondo E flat major op. 16

The genesis of this work is above in the review of Haeun Kim.

I felt Nakagawa’s approach unfortunately lacked grace, panache and élan which I feel this ultimate stye brillante work requires. I was looking for her to caress the melody and play repeated phrases in not exactly the same manner. I felt she could have lifted it out of the virtuoso exercise domain.

c) Impromptu G flat major op. 51

It contained the shadows of joyful gestures but overall was pleasant and played rather as a blithe and attractive work.

d) Nocturne F sharp minor op. 48/2 (1841)

There were some truly lovely, beautiful poetic moments in this performance, but the profound sense of loss was not always apparent. This sublime unbroken song seems endless. That endless melody is what characterizes Chopin above all during the 1840s, in his last, reflective, post-Romantic phase. This is the source of Wagner’s unendliche Melodie.

e) Scherzo C sharp-minor op. 39

This scherzo opens in a ‘Gothic’, almost grotesque manner to become a fine and noble account approaching immense grandeur. Dedicated to his muscular pupil Adolf Gutman, this was last work the composer sketched during the Majorca sojourn and in the fraught atmosphere of the monastery at Valldemossa. The religiosity of the chorale was deeply affecting with its jeu perlé cascades of notes, diamonds falling on crystal. The sotto voce transition to the minor is deeply affecting and existentially tragic in the face of the abyss of death. Chopin was ill at the time which interrupted and perhaps affected the writing. ‘…questions or cries are hurled into an empty, hollow space – presto con fuoco.’ (Tomaszewski).

I felt Nakagawa failed to come to full terms with this demanding work. She was tempted into many solecisms. However, the deeply affecting transition to the minor key was accomplished superbly.

Eugene Nam – Australia

a) Ballade G minor op. 23

Again, the genesis of this work is above in the review of Haeun Kim

I felt Nam conceived an excellent ‘balladeer’ opening as the musical ‘story’ began to unfold. His tone is richly attractive and touch refined. The LH counterpoint was both moving and instructive and indicated that he was telling a ‘story’ in music, naturally not as programme music but as the destiny of feelings through a life. Excellent articulation and keyboard command. His phrasing and rubato were near perfect for this work, as were his rhapsodic dynamic variations. He utilized silence well as a powerful expressive device. Overall the rendition was dramatic yet poetically searching with a strong sense of musical structure.

b) Impromptu F sharp major op. 36

The Chopin genre of the ‘Impromptu’ is a challenge to master. Andre Gide wrote of the Impromptus: The impromptus are among Chopin’s most enchanting works. The great Polish musicologist and Chopin specialist Mieczyslaw Tomaszewski also wrote of them:

The impromptus offer us music without shade, a series of musical landscapes prefiguring impressionism.

The autonomous Impromptu genre was not that well established, even for Schubert, when Chopin composed his first but as the years passed he gave the form his own particular identity.

This was a charming interpretation but after the thoughtful beginning without a great deal of carefree rejuvenated joy or sense of improvisation.

c) Polonaise B flat major op. 71/2

For the genesis and significance of this work refer to the Adam Gozdziewski review above.

Nam was full of self-confidence in this work, especially in the expressiveness. One felt a genuine oscillation between personal feelings and the rather ‘classical’ polonaise genre that came before him. I felt, as mentioned before, that the embedded fiorituras should be caressed and developed depending on the context and not simply ‘tossed off’ as cosmetic excretions.

d) Variations sur „Là ci darem la mano“ B flat major op. 2

For the genesis of this work and interesting details, the review dedicated to Leonhard Krahforst above will assist.I felt the opening by Nam was rather too intense for a set of Variations on a Mozart aria. One should never forget the reverence that Chopin held for Mozart, so I am sure these youthful variations would have attempted to reflect the tasteful character of Chopin’s master. The first statement of the aria was pleasant and lively indicating the naturally gifted musicality of Nam the pianist. His L.H. is a particularly strong and balancing it in counterpoint with the R.H. together with revealing the polyphony within the composition, gave us a satisfactory performance. I found it impressive if lacking a little in period style and atmosphere.

Akhiro Sano – Japan

a) Polonaise B flat minor op. posth

There was nobility in this account but I felt the dynamics not sufficiently varied to be deeply expressive emotionally.

b) Impromptu A flat major op. 29

For a few words on the Chopin Impromptu as a genre look at the notes on Eugene Nam above. Chopin composed the Impromptu in 1837 and published it the following year, dedicating it to one of his pupils, Lady Caroline de Lobau. As Ferdynand Hoesick sees it, the A flat major Impromptu ‘has the brightness of sunlight playing in a fountain’s spray’. In Arthur Hedley’s opinion, it has ‘all the air of a carefree improvisation’, though ‘closer inspection of the first section reveals a skilful hand at work.’ The Impromptu was met with an amusing anonymous review in a periodical issued by a rival publisher – La France musicale. ‘The best thing one can say about this work is that Chopin composed very beautiful mazurkas […] at the end of the fifth page, Mr. Chopin is still seeking an idea… he ends at the bottom of the 9th page, [having failed to find one] by slapping down a dozen chords. Voilà l’Impromptu’.

This was an interpretation without a great deal of internal organic life. A feeling of joyful spontaneity Allegro assai, quasi Presto and improvisation was not as clear as I would have appreciated in this difficult Chopin genre. The more reflective central section, a piano song, was rather moving.

c) Variations brillantes B flat major op. 12

In the 1830s, in Paris, Chopin returned to variations. In 1833 he composed Variations in B flat major, Op. 12, on the theme ‘Je vends des Scapulaires’ from the Hérold/Halévy opera ‘Ludovic‘. This work, elegant, sparkling and of shallow expression, is regarded as a further nod in the direction of the style brillante, this time in the ‘Parisian’ style, bringing little to his oeuvre.

Although this interpretatively difficult work was played with commitment and charm, I felt Sano could have brought a little more panache and élan to his performance.

d) Nocturne F sharp minor op. 48/2

This sublime unbroken Chopin song seems attractively endless. Such a melody is what characterizes Chopin above all during the 1840s, in his last, reflective, post-Romantic phase. This is the source of Wagner’s unendliche Melodie (unending melody).

There were some poetic moments in this performance, but the profound sense of loss depicted in music was not always apparent. We were rather drifting softly through the night.

e) Fantaisie F minor op. 49

The difficulties in bringing together the fragmented nature of the next work, the Fantasy in F Minor Op. 49, are well known. Carl Czerny wrote perceptively in his introduction to the art of improvisation on the piano ‘If a well-written composition can be compared with a noble architectural edifice in which symmetry must predominate, then a fantasy well done is akin to a beautiful English garden, seemingly irregular, but full of surprising variety, and executed rationally, meaningfully, and according to plan.’

At the time Chopin wrote this work improvisation in public domain was declining. Sano brought together all these disparate elements into an enviable unity of expressive intention with well judged expressive rubato. With many of Chopin’s apparently ‘discontinuous’ works (say the Polonaise-Fantaisie) there is in fact an underlying and complexly wrought tonal structure that holds these wonderful dreams of his tightly together as rational wholes.

An expressive performance certainly but seemed to lack a little the feeling of improvised fantasy playing like globes of mercury in the composer’s mind, sometimes merging and sometimes autonomous but never controllable. This being said the account was fluent and authoritative. The devotionals and reflective chorale was most affectingly played followed by a passionate spontaneous eruption of emotion like a volcano of pent up energy released.

As I listened to this great revolutionary statement, fierce anger, nostalgia for past joys and plea for freedom, I could not help reflecting how the artistic expression of the powerful spirit of resistance in much of Chopin is so desperately needed today – not in the restricted nationalistic Polish spirit he envisioned but with the powerful arm of his universality of soul, confronted as we are by yet another incomprehensible onslaught of evil and barbarism. We need Chopin, his heart and spiritual force in 2022 possibly more than ever before.

Seungyeop Sim – South Korea

a) Rondeau à la Mazur F major op. 5 (1825-1826)

This piece was written when Chopin was 16. He dedicated it to the Countess Alexandrine de Moriolles, the daughter of the Comte de Moriolles, who was the tutor to the adopted son of the Grand Duke Constantine, Governor of Warsaw. This rather unpleasant individual, the Grand Duke, often requested Chopin to play for him at the Belvedere Palace. Unable to sleep, on winter nights he would ostentatiously send a sleigh drawn by four-horses harnessed abreast in the Russian style to collect the young pianist from his home. Schumann first heard the Rondo à la mazur in 1836, and he called it ‘lovely, enthusiastic and full of grace. He who does not yet know Chopin had best begin the acquaintance with this piece’. Here, ‘folk’ elements (the ‘Lydian fourth’ in the melody, the stylisation of a country ensemble) are accompanied and augmented with highly bravura virtuoso sections.

There is charm, style, élan and panache in this work which should be brought to the fore with a light touch to create le climat de Chopin as Chopin’s pupil Marcelina Czartoryska referred to the atmosphere surrounding his works. Here in Chopin we have as a young, carefree, Polish adolescent with character and personality plus, wit, humour, theatrics – a young man striving to please with his massively precocious talent.

A period feel is vital for this elegant and exuberant piece. Despite the keyboard discipline and style brillante execution required, I feel it is helpful to ask the question ‘How did Fryderyk Chopin actually live?’. The first question is, can one imagine a world in 2022 without electricity ? Almost everything we take for granted would be absent and the choices of ‘entertainment’ vastly limited. Sim possesses that luminous Korean piano sound that appears inimitable. With some sense of style gave a very good performance.

b) Polonaise B flat major op. 71/2

I wrote about the genesis of this work in my notes on Adam Gozdziewski above. Sim has the expressive nature of the polonaise genre ‘at his fingertips’. Many period emotions were present but emotionally he became rather exaggerated in his presentation of the work.

c) Fantaisie F minor op. 49

My remarks below on the performance by Akhiro Sano of this work may be useful to read. The long introduction is difficult to manage meaningfully and his forte verges on the harsh. The Chorale was very beautiful as he presented it, this introspective pause from considerations of war and defiance. The technical difficulties facing the pianists are not insignificant. The conclusion was affectingly meditative

d) Impromptu F sharp major op. 36

The Chopin genre of the ‘Impromptu’ is a challenge to master. Andre Gide wrote of the Impromptus: The impromptus are among Chopin’s most enchanting works. The great Polish musicologist and Chopin specialist Mieczyslaw Tomaszewski also wrote of them:

The impromptus offer us music without shade, a series of musical landscapes prefiguring impressionism.

The autonomous Impromptu genre was not that well established, even for Schubert, when Chopin composed his first but as the years passed he gave the form his own particular identity.

This was another genre I felt not completely mastered by the candidates. This was a pleasant and considered, thoughtful interpretation but without a great deal of later expressed carefree and rejuvenated joy or sense of improvisation.

Mateusz Tomica – Poland

I was most impressed with much of his Round 1 performance (his fine set of the Mazurkas Op.24 and the Études) and expected some excellent playing from this young tyro in Round 2. I was not disappointed!

a) Polonaise D minor op. 71/1

Chopin wrote his Three Polonaises, Op. 71, probably as early as 1820, though they remained unpublished until six years after his death. In 1855 the works were released although Chopin had asked for his manuscripts to be burned after his death. i was unable to be present at this opening performance of his programme.

b) Barcarolle F sharp major op. 60

The work is a charming gondolier’s folk song sung to the swish of oars on the historic Venetian Lagoon or a romantic canal, often concerning the travails of love, a true song of love. It is a grand, expansive work from the late period of Chopin, written in the years 1845–1846 and published in 1846. Chopin refers in this work to the convention of the barcarola – a song of the Venetian gondoliers which inspired many outstanding composers of the nineteenth century, including Mendelssohn, Liszt and Fauré. Yet surely his barcarolle is incomparable…

As with the Berceuse, Op. 57, the work may be considered ‘music of the evening and the night’ (Tomaszewski). However, it is a far longer work and of immense difficulty. The work is not a contemplative nocturne although there are similarities – it explores many passions of the day and the night. The penumbra of eroticism, Venice and the nature of Italian passions present in the ornamentation is strongly present in this masterpiece with its universal emotions.

Tomica handled the aesthetic fluctuations of mood well and created a charming water colour of the rather contemplative yet fraught emotions of love on the lagoon. This was a good performance but not a particularly individual vision.

c) Rondo C minor op. 1

This work was written by fifteen-year-old ‘Frycek’ and published in 1825. The rondos indicate familiarity with the rondos of the Viennese Classics by Haydn, Mozart Beethoven and lesser luminaries. The dazzling and fashionable style brillante was somewhat of an obsession with the young pianist Fryderyk. However, later in life the scherzos, ballades and études avoided the genre of the free-standing rondo. They are now considered as youthful or virtuosic pieces indicating the ‘classical’ aura of his training in composition. This is not to say they should be glided over without due attention. They are more recently being given more serious attention.

Young Chopin also observed features of the style brillant in rondos by the gloriously blithe Hummel and also Weber. This gave him the model for shaping the pianistic luster of his own works. This Op.1 Rondo is already marked by a graceful, elegant and brilliant writing and can be highly entertaining if performed with the correct feel for context and period.

Tomica brought an alluring, sparkling tone and refined touch to the work in sound. Stylistically it was perfectly correct, taken at a moderate tempo and not hysterically exaggerated. Charming, elegant and stylish. All I would say is that it could have had a trifle more internal energy and drive. Overall an excellent performance reminding us of the budding greatness of the young Chopin.

d) Impromptu A flat major op. 29

A lively performance taken at the possibly correctly joyful ‘up tempo’ but without a feeling of improvisation, which is rather essential to this work. It was certainly spontaneous, lively and a joyful celebration of life. A most enjoyable performance.

e) Ballade G minor op. 23

I strongly suggest you read the genesis notes above for this work contained in my remarks for Haeun Kim. Tomica began as a true ‘balladeer’ narrating a story but in musical emotions. A few solecisms crept in unfortunately in this rather conventional interpretation. However many of the graphic episodes Chopin wrote were presented in a dramatic and exciting fashion. I felt he needed to cultivate more expression coming from the internal details. Many aspects were rushed which disrupted the narrative flow which in turn led to experiencing sensations rather than deep emotional reflections and soulful , spiritual contacts.

Vojtech Trubac – Czech Republic

a) Ballade G minor op. 23

I strongly suggest you read the genesis notes above for this work contained in my remarks for Haeun Kim.

The work opened well with a narrative ‘balladic’ feeling that a musical drama would unfold. The approach the work was dramatic and theatrical, which was arresting and remarkably powerful. At times however, I felt Trubac approached the work as a virtuoso exercise than a charting of spiritual and physical destiny. An entirely valid approach in highly impressive pianism.

b) Variations brillantes B flat major op. 12

In the 1830s, in Paris, Chopin returned to variations. In 1833 he composed Variations in B flat major, Op. 12, on the theme ‘Je vends des Scapulaires’ from the Hérold/Halévy opera Ludovic. This work, elegant, sparkling and of shallow expression, is regarded as a further nod in the direction of the style brillante, this time in the ‘Parisian’ style, bringing little to his oeuvre.

I felt Trubac could have brought some cultural context to bear and a clearer sense of period atmosphere and the sensibility of the day rather than 2022. Certainly the playing was in the style brillante.

c) Polonaise C minor op. 40/2

The general atmosphere of this work is elegiac, even tragic in expression. Arthur Rubinstein remarked that the Polonaise in A major is the symbol of Polish glory, whilst the Polonaise in C minor is the symbol of Polish tragedy. The work features an even rhythm of quaver chords in the right hand and a mournful melody played in octaves by the left, with occasional lines played by the right hand. It is interspersed with a more serene theme, before switching to the trio section in A flat major, which incorporates typical polonaise rhythms.

This was presented as rather a virtuosic piece of theatre with nobility in the main these. The Trio was charming and alluring but perhaps could have been slight more aesthetic in mood (but this is just me!). i felt the expression of this tragic destiny rather unsubtle and expressd without resswrvation. Very much a żal imbued performance.

d) Impromptu A flat major op. 29

This work bubbled along like a mountain stream at an elevated tempo. the theme was articulated detaché instead of legato, but i still felt and excess of pedal. There was a strong element of spiritual resignation at the conclusion.

e) Scherzo B minor op. 20

This work affects me as being formidably disturbed emotionally, even if it is his first scherzo. Trubac gave a strong and convincing declamatory opening. Here he was much the powerful virtuoso pianist driven by a vision. Soft expression was kept to a minimum except when used as a heartbreaking contrast of emotion. Frederick Niecks quotes Robert Schumann who wrote of the Chopin Scherzos (the Italian word scherzo meaning ‘joke’) ‘How is ‘gravity’ to clothe itself if ‘jest’ goes about in dark veils?’.

I really must quote the great Polish Chopin musicologist Miczysław Tomaszewski verbatim as his description of this work simply cannot be bettered by any modest commentary I might make.